The Vandegrifter

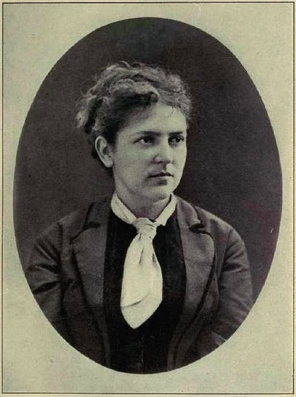

Fanny Van de Grift Stevenson

This project aims to shift attention on Stevenson from biography to literary output, considering her within the context of other late nineteenth century American women writers. Stevenson’s archives comprise boxes on boxes of records held in the National Library of Scotland, the Yale University Library, and the California State Park Archives, as well as the independent Robert Louis Stevenson Museum in St. Helena where these manuscripts are held.

Stevenson has always occupied a metamorphic, ambiguous space in critical and literary historical memory. Historians and biographers have tended to polarise depictions of her life as one of either overwhelming self-sacrifice and romance, or one of calculating manipulation and unkindness. In neither case do these various accounts Stevenson’s life position her as a writer or artist, despite both of those occupations being her lifelong interests. At most, such narratives have described Stevenson as a storyteller. As Heather Waldroup argues, “Stevenson certainly takes pleasure in describing, in the telling of a story … her life experience gave her a knack for interpreting and explaining narratives around her.”[4] Stevenson's letters, stories, and other writing capture her dry wit, and her talent for weaving captivating tales.

As an example, Stevenson notes in a diary entry from 1894 that a guest at their home in Apia, Samoa, had been particularly irritating. Stevenson describes the problematic visitor, dubbed “the Frenchman,” with her characteristic sarcasm. Though the man may have been “quite clever in many ways,” he is reportedly “beyond measure wearisome with long complicated boastful stories about himself, most of them patently false.” Though the man calls himself “a dreamer,” Stevenson muses, “I think him a nightmare” (1894). Her letters and diaries are full of such compelling and incisive reflections, but have seldom been critically acknowledged, especially those from before the famous Stevenson family voyage to––and settlement in––Samoa.

Every scholar and writer presents wildly different conceptions of how Stevenson impacted those around her. Stevenson’s sister, Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez, affirms the potential of Stevenson's literary accomplishments, considering that, if her sister had not chosen to “devote her time and strength to … the support and encouragement of others, there is no saying how far she might have gone, for she had an active, creative imagination, and a discriminating, critical judgment of style.” In one evocative description, Sanchez calls her a “sort of spiritual X-ray” capable of discerning someone’s character almost immediately.[5] All her life, Stevenson was plagued by anxiety and shyness, and she did not like to talk about her own work, even though she was in the public eye for much of her life.

Stevenson also maintained a close friendship with Henry James, whom she had met through her husband, but remained close with long after Louis's death. Rumours have often circulated surreptitiously that various stories and novels by James, some quite celebrated, took the Stevensons as inspiration: he was reportedly fascinated by the Stevensons’ marriage and collaborative spirit. Indeed, Stevenson and Louis regularly collaborated, either on plays, their 1885 volume The Dynamiter, or on more daily tasks such as scribing, rewriting, or editing.

In her introductions to Louis’s volumes and in her letters, Stevenson deflects from her contributions to his writing, despite her husband openly acknowledging such efforts in his own letters and papers. Some of her letters point towards Stevenson's fraught relationship with the idea of writing for a living: she wrote to her mother-in-law, Margaret Stevenson, in March 1881, concerned about her son Lloyd, who was uninspired by his studies. “So far,” Stevenson writes, “he seems to show no bent for anything more than literature, and that is an uncertain reed to lean upon.”[6] The “uncertain reed” of public authorship, though, did not stop Stevenson from writing on her own terms, to her own ends. In correspondence with Sidney Colvin in May 1889, Stevenson details her frustration with Louis’s equivocation over writing a volume on their Pacific travels. Stevenson laments that, with her “own feeble hand,” she could “write a book that the whole world would jump at.” However, in the preface to Stevenson's own travel narrative, The Cruise of the Janet Nichol (1914), she declares that the whole diary was “only intended to be a collection of hints to help [her] husband’s memory” as he wrote his own accounts.[7]

The tension between Stevenson’s bold claim in her letter to Colvin and the latter modesty indicates some of the many sacrifices Stevenson made in her own writing in order to support her husband's career. This project serves to intervene into these imbalances and amplify Stevenson’s unpublished writing for the first time, as part of an under-acknowledged tradition of late nineteenth century women’s writing, rather than as an auxiliary of her husband.